Trends in Wine Consumption (1967-2012) from Atlas de la vigne et du vin

One of the more remarkable propositions in Legouy and Boulanger’s excellent Atlas de la Vigne et du Vin (2015) is that whilst wine consumption in France and Italy has steadily declined over the past forty years, wine consumption in Britain has exploded. Red, white, and rosé are colours that are brightening social occasions more and more frequently. What has changed then among the Britons whom the French King Charles VII, during the Hundred Years War, told to ‘go back home and drink that ale you’re so used to’?

A democratisation of wine

It is no longer just the elite who are drinking wine, nor is all wine expensive. All the major newspapers now have wine columnists, and wine is much discussed on television, not to mention the internet. With the massive growth of flights and holidays to Mediterranean resorts, Britons now frequently encounter places which have their own long traditions of wine production and consumption. At home, wine is also very present in the socialising that forms a large part of soap operas like Eastenders and Coronation Street. The terraced houses of the fictional Coronation Street differ in many ways from the high-ceilinged rooms of the fictional Downton Abbey, yet both represent Britons consuming wine at ease. The popping of a cork and the golden bubbles of sparkling wine can now, in the form of Prosecco and Cava, be had for half of the price of the cheapest Champagne, and the rich and powerful reds of Bordeaux and Châteauneuf-du-Pape can now be left on the shelf when cheaper Californian and Australian wines made with the same grape varietes are widely available.

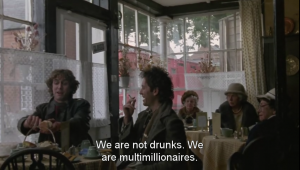

The spaces and times in which wine is drunk have significantly changed over the past forty years. There are now, for instance, fewer long lunches in restaurants and glasses of sherry in the afternoon, and more post-work drinks, catching up with friends over a bottle of wine, and wine accompanying ordinary weekday dinners. Wine bars have spread, pubs serve a wide range of wines, and even small cafés, where traditionally only porcelain would clink, now often resound with the chiming of wine glasses. Withnail’s demand for ‘the finest wines available to humanity’ in a village tea room of the Lake District in the 1970s might now, in 2016, be at least partly fulfilled.

New wines, new times

Historically, the English and then British taste for wine has done much to influence, even invent wine production overseas. Port, Sherry, Madeira and Marsala are fortified wines that owe a great deal to the famed British sweet tooth, whilst the wines of Bordeaux and Champagne flourished through being exported to England, as the French Historical Geographers Roger Dion and Xavier de Planhol explained.

In the 1960s and 1970s Britons began to eat out in large numbers. Restaurants grew in number and variety and offered more affordable meals, and many people began to enjoy a little more disposable income. A handful of famous brands of wine were often seen accompanying meals in the 1970s, including the German Liebfraumilch ‘Blue Nun’ and the evocatively named Hungarian ‘Bull’s Blood’. Sherry and Port also still had their place in some houses before and after the evening meal. Since then, the range of wines drunk in Britain has grown, and the wines of the New World have become particularly widespread. Marketed on the basis of grape variety, Merlots, Chardonnays, and Sauvignon Blancs from California, Australia, Chile and New Zealand are now seen on menus, behind bars and on supermarket shelves up and down the country.

The world of wine does still retain something of its aspirational character in British society, and it has its legendary names, its fads and its faux pas like any other middle-class pursuit (fashion, gourmet coffee and skiing come to mind). There is of course still a buoyant market for Bordeaux First Growths, Burgundy Grands Crus, and other fine wines, especially in London. Yet where wine was once the privilege of the few, it is now firmly established as the drink, and the culture, of many. The much-debated Brexit will do little to curb the taste of Britons for wine; it may even offer a boost to the British wine industry which has itself grown substantially in recent years.

A wider Anglophone adventure

The trend towards greater wine consumption in recent decades is also evident in the United States, Canada and Ireland. Indeed, statistics available from the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (www.oiv.int/en/databases-and-statistics/statistics) show us that whilst the average consumption of wine in the UK roughly doubled from 13.5 litres per person in 1995 to 26.6 litres in 2005, for that same ten-year period in Ireland the consumption went from 5.7 to 20.7 litres, appearing to have almost quadrupled!

Thus in the English-speaking territories of the northern hemisphere, where the landscapes of sun-drenched vineyards are more imagined than lived, wine is becoming an ever more domesticated, popular and well-known drink; a symbol of changing culinary culture and new ways of sharing some joie de vivre. Cheers !

Rory Hill is a British geographer and a research scholar at the Food 2.0 LAB ; his works focuses on French terroir.